|

TESTI BIOGRAFICI IN INGLESE THESE TEXTS ARE IN ENGLISH

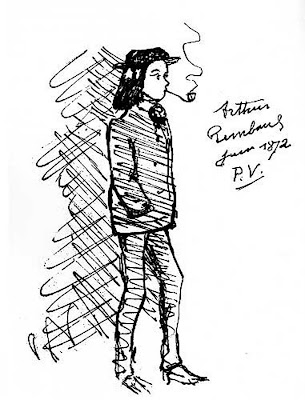

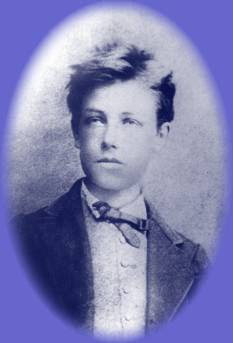

~ * ~ * ~ * ~ * ~ "The Child of Anger" "The Infernal Husband" "The Man with Foot Soles of Wind" ...................... "The man was tall, well-built, almost athletic, with a perfectly oval face of an angel in exile, with untidy light brown hair and eyes of a disturbing pale blue" - Paul Verlaine: The Accursed Poets ~ ~ ~ "This Considerable Passer-By" ...................... "Glare, him, of a meteor, lit without any other motive than his presence, born alone and dying out". "... the one, who rejects dreams, by his fault or theirs, and operates on himself, alive, for poetry, later can find only far, very far, a new state. Oblivion includes the space of the desert or the sea." - Stéphane Mallarmé: letter to M. Harrison, Rhodes. "Arthur Rimbaud", The Chap Book Review, May 15, 1895 and Divagations, 1897 ~ ~ ~

CONTENTS:

From Poet to Adventurer: A BIOGRAPHY

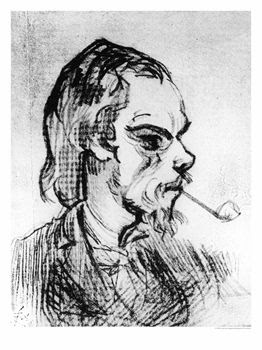

Jean Nicolas Arthur RIMBAUD was born in Charleville, in the Ardennes, on October 20, 1854. His father, Captain of Infantry Frédéric Rimbaud and his mother Vitalie Cuif, who came from a farming family of Ardennes, married in 1853. Arthur had an elder brother, Frédéric and two sisters, Vitalie and Isabelle, respectively born in 1858 and in 1860. MORTAL, angel AND demon, as to say Rimbaud, You deserve the first place in this book of mine, Despite of such smart scribbler called you a beardless ribaud*, And a budding monster, and a drunken schoolboy. The first place yet in the temple of Memory All the spirals of incense, all the chords of lute! And your radiant name will sing in the glory, Because you loved me as it had to be. The women will see you, tall young man very strong, Very handsome of a rustic and wily beauty, With an indolently daring attitude; History sculptured you triumphing over death Omnipotent Poet and victorious of life, Your white feet put on Envy's heads. Paul Verlaine - As published for the first time in the review "Le Chat Noir" (The Black Cat) on August 24, 1899. ~ *A ribaud is a debauched person.

…AND ANOTHER BIO TOO…: (a bit more succint, if you’re in a hurry) Arthur Rimbaud (1854-1891)

French poet and adventurer, who stopped writing verse at the age of 21,

and became after his early death an inextricable myth in French gay life.

Rimbaud's poetry, partially written in free verse, is characterized by

dramatic and imaginative vision. "I say that one must be a visionary -

that one must make oneself a VISIONARY." His works are among the most

original in the Symbolist movement, which included in France such poets

as Stéphane Mallarme and Paul Paul Verlaine, and playwrights as Maurice Maeterlinck.

Rimbaud's best-known work, LE BÂTEAU IVRE (The Drunken Boat), appeared in 1871.

In the poem he sent a toy boat on a journey, an allegory for a spiritual quest. What? Eternity. It is the sea Gone with the sun. (from 'L'Éternite', 1872)

Arthur Rimbaud was born in Charleville, in the northern Ardennes region of France, as the son of Fréderic Rimbaud, a career soldier, who had served in Algria, and Marie-Catherine-Vitale Cuif, an unsentimental matriarch. Rimbaud's father left the family and from the age of six young Arthur was raised by her strictly religious mother. Rimbaud was educated in a provincial school until the age of fifteen. He was an outstanding student but his behavior was considered provocative. After publishing his first poem in 1870 at the age of 16, Rimbaud wandered through northern France and Belgium, and was returned to his home in Paris by police.

Dans la feuillée, écrin vert taché d'or, Dans la feuillée incertaine et fleurie De splendides fleurs où le baiser dort, Vif et crevant l'exquise broderie, Un faune égaré montre ses deux yeux Et mord les fleurs rouges de ses dents blanches. Brunie et sanglante ainsi qu'un vin vieux, Sa lévre éclate en rires sous les branches. Et quand il a fui - tel qu'un écureuil, - Son rire tremble encore à chaque feuille, Et l'on voit épeuré par un bouvreuil Le Baiser d'or du Bois, qui se recueille.

Selected works:

• UNE SAISON EN ENFER, 1873 - A Season in Hell • ILLUMINATIONS, 1886 - (ed. by Paul Verlaine) • LE RELIQUAIRE, 1891 • POÈMES, 1891 • POÉSIES COMPLÈTES, 1895 (publ. by Verlaine) • LETTRES, 1899 • LES MAINS DE JEANNE-MARIE, 1919 • ŒUVRES COMPLÈTES, 1921 • UN CŒUR SOUS UNE SOUTANE, 1924 • LETTRES (1870-1875), 1931 • ŒUVRES, 1931 • POÉSIES, 1939 • ŒUVRES COMPLÈTES, 1946 • CORRESPONDANCE 1888-91, 1970 • Arthur Rimbaud: Complete Works, 1976 • Rimbaud Complete Works: Selected Letters, 1987 • Rimbaud: Poems, 1994

…AND SOME MORE: (because I like it!) THE STRANGE FATE OF ARTHUR RIMBAUD, BOY POET by Pierre Ferrand

Arthur Rimbaud (1854-1891) is undoubtedly one of the most puzzling figures among the world’s famous poets. As a result, he has been the subject of endless controversy, and he is forever quoted and interpreted out of context.

~ Here's a fair translation of Rimbaud's... As I was descending cold-faced rivers, I realized I had lost my guides: Yelping Redskins are taking them for targets, They've nailed them naked to painted poles. I didn't give a fuck about the crew or cargo Of Flemish wheat and English cotton. When the screams of my haulers had finally ended, The rivers let me go where I wanted. In furious tongues of surf last winter I, being deffer than a child's brain, Ran! And the peninsula took off Unused to such triumphant noise. The storm has blessed my awakening. More light than a cork I dance on the waves That are called the eternal rollers of victims, Ten nights, without missing the inane look of the lanterns. More sweet than the flesh of sour apples to boys The green water entered my hull of fir And washed the vomit and blue wine Off me, scattering rudder and grappling hook. And from then on I bathed in the Poem Of the Sea, star-soaked, milk radiant, gulping Down the green sky-blue; where the pallid debris Is stirred by the drowned man's passing thoughts. Where all of a sudden the blueness is dyed: madness And slow rhythms under the gleam of day, Stronger than alcohol, more vast than our song, The bitter red dots of love ferment! I know the skies bursting with lightning, and the waterspout And the undertow and the currents: I've been the evening, The Dawn, as elated as the nation of doves, And at times I've seen what man believes he's seen! I've seen the setting sun, stained with mystical horror, Light up the long purple jellies Like actors of ancient dramas The waves roll away their quivering shutters! I've dreamed the green night of dazzling snows, A kiss wells up slowly to the eyes of the sea, The circulation of previously unimaginable saps, And the yellow and blue dawn of crooning phosphor! I have followed for many ripe months the cowish Hysterical pounding of swells on the reefs, Without supposing that the glowing feet of the Marys Could kick in the face of the wheezing seas! I have hit upon, understand, unbelievable Floridas Mingling with flowers the eyes of panthers-in- Man-skin! The rainbows tight as reins Beneath the oceans to some glaucous flocks! I have seen the enormous swamp ferment, fish-net Where in the rushes rots a prehistoric whale! Water collapse cascading in the midst of calm, And distances that lead to a torrential emptiness! Glaciers, silver suns, nacreaous waves, glowing embers of sky! Hideous wreckage on the floor of brown gulfs Where the giant snakes devoured by bugs Sink, like torn trees, in black perfumes! I would have loved to show the children these gilt-heads From the ocean blue, these fish of gold, these fish that lyricize. --Flower foam rocks my formless drift And ineffable breezes make wings of me at times. Sometimes, a martyr weary of zones and poles, The sob of the seas gentled my rocking, Lifting its flowers of shadow on yellow suction pads And I stayed there, like a kneeling woman... Nearly an island, tossing around my banks the quarrels And dung of blond-eyed birds. And I sailed along, as across my frail lines Drowned men sank to sleep backwards! Thus I, boat lost beneath the hair of coves, Thrown by the storm into birdless ether, I, the ruin drunk with water, would not Have been rescued by the Monitors of Hanseatic caravelles; Free, smoking, lifted by the purple mist, I who pierced the smoldering sky like a wall Which offers good poets that exquisite jam The lichen of the sun and infinite-blue mucous; Who ran, stained by electric half-moons, Loony board, escorted by black sea-horses, When the Julys were thrashing and smashing The sea-blue skies of burning funnels; I who was shaking, feeling fifty miles away the moan Of the rutting Hippos and the thick Maelstroms, I the eternal plyer of the blue immobilities, I miss the Europe of ancient parapets! I've seen sidereal archipelegos! and islands The delerious skies of which are open to the wanderer --Is it in these ancient nights that you sleep and exile yourself, Millions of golden birds, oh future Strength?-- But really, I cry too much! The Dawns are beyond hope. Any moon is atrocious and any sun bitter: The acrid love inflated me with its heady torpors. Oh that my keel explode! Oh that I'm all the sea! If I desire the waters of Europe, it's the puddle Black and cold, where towards fragrant twilight A squatting child full of sadnesses, releases A boat as frail as a butterfly. I can't anymore, bathed in your languors, oh waves, Erase the traces of your cotton carriers, Nor traverse the arrogance of flags and flames, Nor swim beneath the horrible eyes of slave ships. The Crux of Rimbaud's Poetics by Eric Mader-Lin

Arthur Rimbaud--the meaning of Arthur Rimbaud's work--has periodically haunted me since I first read him in English translation at age 16. It was around a year after my first reading of Rimbaud that the following lines appeared in my high school's literary magazine over the name Delahaye:

Car Je est un autre. Si le cuivre s'eveille clairon, il n'y a rien de sa faute. Cela m'est evident: j'assise a l'eclosion de ma pensee: je la regarde, je l'ecoute: je lance un coup d'archet: la symphonie fait son remuement dans les profondeurs, ou vient d'un bond sur la scene.

Here again, cited for the thousandth time, is that locus classicus of modern poetry, the lettre du voyant. We have encountered it so many times we finally become indifferent to the meaning of its formulae. The first thing we always remark upon reading over these lines is that the process of Rimbaud's poetics is quite explicit. One could "easily" become a disciple of Rimbaud by taking up this project step by step. The very explicitness of his formulae has perhaps rendered his poetics somewhat opaque. For what is not explicit are the implications of this project. And we have become so used to reading mere restatements of this project that we neglect to think through what these implications might be. What is the philosophy it implies? I would say even: What is the theology implied in Rimbaud's theory of the voyant? What would the universe need to be for Rimbaud's project to bring forth the results he so fervently hopes it will? It is only through questions such as these that we may approach the young poet's thought.

2) This is a potential in language that needs to be tapped. 3) The voyant is the only one capable of tapping this potential. 4) To tap this potential in language is to approach creating the "universal language." 5) The universal language is capable of transforming the world. 6) The universal language is already somehow latent in language as potential. 7) The voyant, as expeditor of the universal language, is a divine being.

Here, in a few positive statements, is Rimbaud's philosophy of language. It is not, as it stands, a necessarily magical philosophy of language, though it does owe much to 19th century occultism. As regards this latter, however, I do not think that Rimbaud believed in a lost Adamic language as the Kabbalists do. His idea of the power in language was not founded on the supposition of something precious that had been lost, but rather on the supposition of things that were there to be found or created. These things to be found or created would give the voyant the power to transform the world. Rimbaud’s notion of the approach to these things was a religious one, and it formulated itself in a kind of praxis: "one must make oneself a voyant." Rimbaud's philosophy of language was not fundamentally magical, but was rather what I would call dispensational.

Cette langue sera de l'ame pour l'ame, resumant tout, parfums, sons, couleurs, de la pensee accrochant la pensee et tirant.... Enormite devenant norme, absorbee par tous, [le poete] sera vraiment un multiplicateur de progres!

Here it is not a question of the power of language to transform things immediately, but rather a question of the power of language to transform men's relations to things. In line with both Western religious tradition and the progressive thought of his century, Rimbaud knew that a transformation of the world meant first of all a transformation of men. Parting ways with his century, however, he understood that the keys to the transformation of man were hidden away somewhere in the Divine.

NOTES

2. I have modified the translation by Wallace Fowlie. Below I will use his translation, unmodified, of Le Bateau ivre. 3. The assumption of the possibility of a universal language in Rimbaud's sense does not necessarily presume an understanding of words as symbols somehow positively holding their meaning. I do not think Rimbaud believed there are hidden syllables which, once uttered, would somehow magically transform reality. This is to say that the possibility of a language capable of overturning the world is not annulled by post-Saussurean linguistics. One need only consider, by analogy, how much of the world Marxism overturned in order to verify the fact of language's potential. 4. Though perhaps he came close. How shall we know? 5. Cf. "The Sleep of Rimbaud" in Maurice Blanchot: The Work of Fire, tr. Charlotte Mandell, Stanford University Press: 1995.

TRANSLATING POETRY THE WORKS OF ARTHUR RIMBAUD FROM FRENCH TO ENGLISH by Michael C. Walker

Few writers depend so heavily on the intricacies of a given language as the poet, for whom each word is often essential. Every major language can provide examples of fine poetry, rich in the demeanor and presence of language, filled with the richness that makes a language unique and interesting. Some would argue that without the variance found in dissimilar languages poetry would fail us as a comprehensive art; could we have the peculiar grammar of Emily Dickinson beside the lyricism of Baudelaire if both poets were constrained to the same language? However, such richness provides difficulty for those who are called upon to translate poetry from one language to another, a common task in the case of well-known poets and a growing area of interest for the works of lesser-known contemporary poets. This article examines issues germane to the translation of poetry using the works of the nineteenth century French poet Arthur Rimbaud as its example. ~ ~ ~ * ~ ~ ~

PAUL VERLAINE AND ARTHUR RIMBAUD, DAMNED GAYS INTRODUCTION

Ô vive lui, chaque fois Que chante son coq gaulois. are often rendered as though the French Cock is just any other gallic rooster…. The coq gaulois or “French Cock” — or so my poor French leads me to understand — is actually a splendid breed of fowl, long an icon of France but more than that, in this case symbolises Verlaine in both his sexual and literary personas. To translate otherwise is to destroy the whole figure of speech, the compacted symbolism for which the youthful Rimbaud became famous. A literal and sanitized translation loses the joy which is so evident in this poem, the joy — in my understanding — of a young man who has discovered that he, like other men, can love and perhaps more specifically, that he can “do sex”. The “saisons” of the title for me are more like Shakespeare’s “ages of man” and the châteauxare castles in the air, the daydreams, young men have about being a man (and which in French are châteaux en Espagne, castles in Spain). Presented by Bob Hay PAUL VERLAINE AND ARTHUR RIMBAUD, PÉDÉS MAUDITS

Le ciel est, par-dessus le toit Si bleu, si calm!

“Le ciel est par-dessus le toit….” is a prison poem and the patch of blue is the only bit of the “outside” which the poet, Paul Verlaine could see from his cell window. In the past half-century, this “patch of blue” has become a symbol for me too, but not so much of freedom from physical confinement, but more from the psychological constraints we place upon ourselves in our daily lives. Over the years I also have used this “patch of blue” in my own writing, a couple of times when talking about “coming out” in the Gay Liberation context and most recently, not long after my mother died, in another essay where I examined the strange double-edged sword the death of a loved-one can sometimes be. I don’t remember what was said in that distant class, but knowing what I know now, I doubt if the poet, Paul Verlaine, ever felt truly free.

LE COEUR VOLÉ Mon triste coeur bave à la poupe, Mon coeur couvert de caporal : Ils y lancent des jets de soupe Mon triste coeur bave à la poupe : Sous les quolibets de la troupe Qui pousse un rire général, Mon triste coeur bave à la poupe, Mon coeur couvert de caporal.

It is at this period while back home in Charleville, Rimbaud seems to have undergone some kind of poetic rebirth and, like Mallarmé before him, revised his whole philosophy of poetry and what it meant to be a poet. rational deregulation of all the senses. All forms of love, of suffering, of madness: he searches himself, he exhausts all poisons in himself, in order to preserve only their quintessence…..”

There can be little doubt the experiences of the past few weeks, the hardship and chaos of the Commune and the trauma of the rape, had ‘deregulated the senses’ and brought about this change in Rimbaud’s thoughts and feelings about poetry.

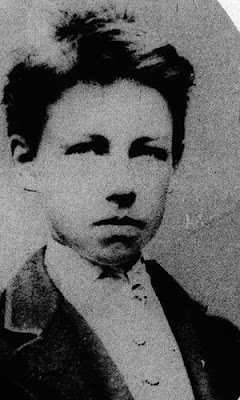

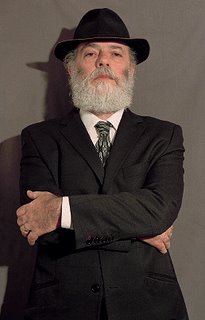

“The man was tall, well-built, almost athletic, with the perfectly oval face of an angel in exile, with untidy light brown hair and eyes of a disturbing pale blue"

Despite his publications, these were bad years for Verlaine who was sinking more and more into debauchery and illness. His mother attempted to rescue him by taking him to the country to live but he scandalised the neighbourhood with his constant drunkenness, his seductions of local farm boys, and finally, by his violence to his mother. For this last, he was once again sent to prison. CHANSON D’AUTOMNE Les sanglots longs Des violons De l'automne Blessent mon coeur D'une langueur Monotone. Tout suffocant Et blême, quand Sonne l'heure, Je me souviens Des jours anciens Et je pleure; Et je m'en vais Au vent mauvais Qui m'emporte Deçà, delà Pareil à la Feuille morte.

In another poem, “Art Poétique” which he wrote in 1874 but which was not published until the collection “Jadis et Naguère” appeared in 1884, Verlaine set out his musical view of poetry: De la musique avant toute chose, Et pour cela préfère l’Impair, Plus vague et plus soluble dans l’air, Sans rien en lui qui pèse ou qui pose……

However, of the two men, it was the teen-age Rimbaud — now virtually canonised in Charleville, the town he kept running away from — who laid the foundations for much of modern literature and contributed most to our modern view of the world. Among others, Rimbaud strongly influenced Joseph Conrad, Jean Cocteau, Hart Crane, Bob Dylan, Jean Genet, André Gide, Allen Ginsberg, William Faulkner, Henry James, James Joyce, Jack Kerouac, Federico García Lorca, H.P. Lovecraft, Marcel Proust, Patti Smith, Oscar Wilde, Virginia Woolf, the Surrealists and much of today's alternative music scene. One such was Jim Morrison (1943 – 1971) and his group, The Doors. Poet as well as musician, Morrison once wrote: LE CHANT DES VOYELLES A noir, E blanc, I rouge, U vert, O bleu : voyelles, Je dirai quelque jour vos naissances latentes : A, noir corset velu des mouches éclatantes Qui bombinent autour des puanteurs cruelles, Golfes d'ombre ; E, candeurs des vapeurs et des tentes, Lances des glaciers fiers, rois blancs, frissons d'ombelles ; I, pourpres, sang craché, rire des lèvres belles Dans la colère ou les ivresses pénitentes ; U, cycles, vibrement divins des mers virides, Paix des pâtis semés d'animaux, paix des rides Que l'alchimie imprime aux grands fronts studieux ; O, suprême Clairon plein des strideurs étranges, Silences traversés des Mondes et des Anges : - O l'Oméga, rayon violet de Ses Yeux ! (Poésies 1870 - 1871) I'll tell One day, you vowels, how you come to be and whence. A, black, the glittering of flies that form a dense, Velvety corset round some foul and cruel smell, Gulf of dark shadow; E, the glaiers' insolence, Steams, tents, white kings, the quiver of a flowery bell; I, crimson, blood expectorated, laughs that well From lovely lips in wrath or drunken pentinence; U, cycles, the divine vibrations of the seas, Peace of herd-dotted pastures or the wrinkled ease That alchemy imprints upon the scholar's brow; O, the last trumpet, loud with strangely strident brass, The silences through which the Worlds and Angels pass: -- O stands for Omega, His Eyes' deep violet glow! (Translation by N. Cameron, 1947)

Now this of course is a sonnet, but note the rhyme scheme in the French: in the quatrains, abba baab and in the tercets, cc deed. And note too the neologism, “bombinent”, presumably from the nonexistent verb “bombiner, to buzz or drone” which Rimbaud invented from the Latin bombus, drone. These features aside, however, this poem is regarded by many as the most modern of all Rimbaud’s texts, especially because it places the associations of words ahead of the meaning of words. It is also an extraordinarily clever construction: notice how he arranges the poem according to the properties of light, first from the darkness of Black to the light of White, then groups the colours in order of the spectrum. This poem is extraordinary too in the way it shows how the poet can play with words yet, like John Donne, leap with them into Eternity. Although brief, the relationship between Verlaine and Rimbaud has continued to preoccupy the curiosity of the public and scholars alike. Two frequently asked questions are “To what extent were they ‘homosexual’ in our sense of the word?” and “How did their sexualities affect their art?” These questions are not motivated by some prurient interest in the sex lives of the two young poets but arise in the attempt to understand how the identity of artists, particularly those who are members of minority groups, affect their art. Similar questions are asked about many feminist and black writers. VERS POUR ETRE CALOMNIE Ce soir je m'étais penché sur ton sommeil. Tout ton corps dormait chaste sur l'humble lit, Et j'ai vu, comme un qui s'applique et qui lit, Ah ! j'ai vu que tout est vain sous le soleil ! Qu'on vive, ô quelle délicate merveille, Tant notre appareil est une fleur qui plie ! O pensée aboutissant à la folie ! Va, pauvre, dors ! moi, l'effroi pour toi m'éveille. Ah ! misère de t'aimer, mon frêle amour Qui vas respirant comme on respire un jour ! O regard fermé que la mort fera tel ! O bouche qui ris en songe sur ma bouche, En attendant l'autre rire plus farouche ! Vite, éveille-toi. Dis, l'âme est immortelle ?

One of my favourite poems, and the one which is most often quoted as expressing Verlaine’s love for Rimbaud is a poem he wrote in prison and which he dedicated to his distant lover. It refers to Rimbaud’s earlier poem which opens thus: Il pleut doucement sur la ville. Quelle est cette langueur Qui pénètre mon coeur?

The third poem of the section of “Romances sans paroles” entitled “ariettes oubliées” (an ariette is a musical movement, a melody), Verlaine made obvious connection to his former lover’s poem, equating the rain with his own tears….. IL PLEURE DANS MON CŒUR Il pleure dans mon coeur Comme il pleut sur la ville, Quelle est cette langueur Qui pénètre mon coeur? 0 bruit doux de la pluie Par terre et sur les toits ! Pour un coeur qui s'ennuie 0 le chant de la pluie ! Il pleure sans raison Dans ce coeur qui écoeure. Quoi ! nulle trahison ? ... Ce deuil est sans raison. C'est bien la pire peine De ne savoir pourquoi Sans amour et sans haine Mon coeur a tant de peine! (Romances sans paroles 1874)

However, to use Carolyn A. Durham’s words, not all of Verlaine’s poems are so evocative of “melodic and bittersweet etats d'ame”. In 1891, Verlaine completed 15 poems celebrating male-male sexuality. This work, Hombres, was not published in his lifetime and indeed, was not included in the Pleiade edition of the poet's complete works until 1989. These are often very explicit, even more accurately descriptive of malemale sex than the famous poem “A day for a lay” by WH Auden which was circulated anonymously when I was still a student but which you can now buy in books, fully attributed, from Amazon.com. While many have rushed to call Hombres plain pornography, in my own view (and I have not yet read them all), they have been damned more because they brilliantly celebrate taboo experiences than for any lack of artistic merit. Ô SAISONS, Ô CHATEAUX Ô saisons ô châteaux, Quelle âme est sans défauts ? Ô saisons, ô châteaux, J'ai fait la magique étude Du Bonheur, que nul n'élude. Ô vive lui, chaque fois Que chante son coq gaulois. Mais ! je n'aurai plus d'envie, Il s'est chargé de ma vie. Ce Charme ! il prit âme et corps. Et dispersa tous efforts. Que comprendre à ma parole ? Il fait qu'elle fuie et vole ! Ô saisons, ô châteaux ! Et, si le malheur m'entraîne, Sa disgrâce m'est certaine. Il faut que son dédain, las ! Me livre au plus prompt trépas ! - Ô Saisons, ô Châteaux ! "Une saison en enfer" 1872/3 republished in "Les lluminations", 1886.

However, I don’t think such censorship is always the fault of squeamish editors: sometimes too, it looks to me as though Verlaine and Rimbaud deliberately left things a little indefinite. Many homosexual poets and song-writers have written in code or in some way hidden their real meaning from all but the cognoscenti. A good example, more or less of our own time, is the American song-writer Jerome Kearne who wrote a song “Can’t help lovin’ that man of mine”. This was a big hit in its day and was sung on stage by a woman but everyone who was anybody knew “that man of mine” was Jerome’s own partner. LE CIEL EST PAR DESSUS....* Le ciel est, par-dessus le toit, Si bleu, si calme! Un arbre, par-dessus le toit, Berce sa palme. La cloche, dans le ciel qu'on voit, Doucement tinte, Un oiseau sur l'arbre qu'on voit, Chante sa plainte. Mon Dieu, mon Dieu, la vie est là, Simple et tranquille. Cette paisible rumeur-là Vient de la ville. -Qu'as-tu fait, ô toi que voilà Pleurant sans cesse, Dis, qu'as-tu fait, toi que voilà, De ta jeunesse? (Sagesse, 1881) _____________________________ * This poem was set to music by many composers including Benjamin Britten (1913-1976) , "Sagesse", from Quatre chansons françaises, no. 2.; Frederick Delius (1862-1934) , "Le ciel est, par-dessus le toit" , 1895, from Songs to poems by Paul Verlaine, no. 2.; Gabriel Fauré (1845-1924) , "Prison" , op. 83 no. 1 (1894), published 1896.; Reynaldo Hahn (1875-1947) , "D'une prison"

ARTICLES ON RIMBAUD ARTICLES: [click titles]

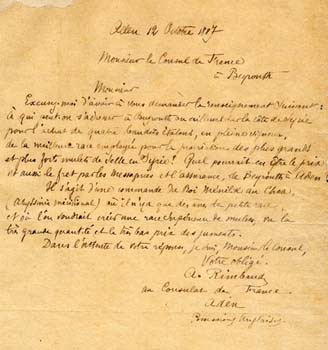

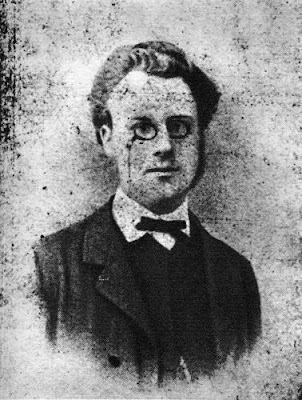

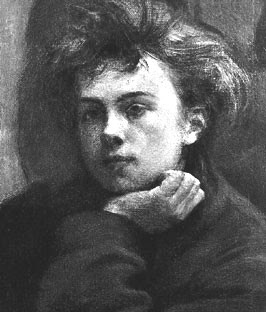

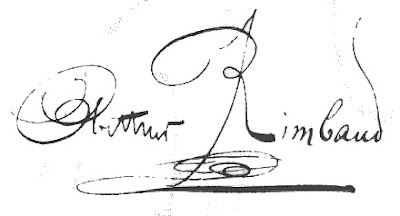

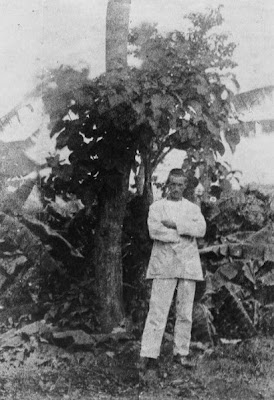

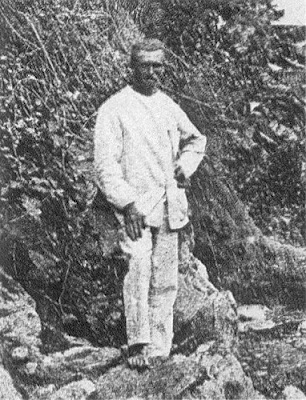

UNDER HER WINGS: GREEN FAIRY’S POETIC REVOLT “The Green Fairy” is the English translation of La Fee Verte, the affectionate French nickname given to the celebrated absinthe drink in the nineteenth century. The nickname stuck, and over a century later, "absinthe" and "Green Fairy" continue to be used interchangeably by devotees of the potent green alcohol. Mind you, absinthe earned other nicknames, too: poets and artists were inspired by the "Green Muse"; Aleister Crowley, the British occultist, worshipped the "Green Goddess". But no other nickname stuck as well as the original, and many drinkers of absinthe refer to the green liquor simply as La Fee - the Fairy [check Rimbaud’s poem by the same title]. Absinthe and the poet go together like a horse and carriage. The metaphorical Green Fairy first earned her fitting reputation as the artist's muse in the second part of the nineteenth century, when she became the drink of choice among the avante-garde habitues of the Latin Quarter, the artistic district of Paris. It was here, in the absinthe-soaked atmosphere of cafes such as La Nouvelle-Athenes and L'Academie where the Symbolist movement was born. It was under the Fairy's wings where the old was being rejected and the new embraced. It was the Fairy who was the witness to, or perhaps the inspirer of, a profound artistic rebellion. ARTHUR RIMBAUD: GREEN FAIRY'S WILD CHILD  Rimbaud hated being photographed; he attacked Carjat, the photographer, with a cane shortly after this picture was taken (1871). Et voilà! Here's Arthur Rimbaud, the first "punk poet", the iconic rebel, and perhaps the most celebrated of all absinthe drinkers. THE REBEL ARRIVES... The appearance of young Rimbaud -- he was only 17 at the time -- in Parisian literary circles was met with a bizarre mix of admiration, jealousy, shock and nervous consternation: "We are witnessing the birth of a genius," declared Leon Valade after attending a dinner of the Vilains Bonshommes, a group of poets to whom Rimbaud was "exhibited" in October 1871. "... a terrifying poet," Valade recalled, "a truly childlike face which might suit a thirteen year old, deep blue eyes, wild rather than timid -- this is the lad whose imagination, with its amazing powers and depravity, has been fascinating or frightening all our friends." ...AND HE SHOCKS FROM DAY ONE At that very first dinner, Rimbaud gave the astonished poets a taste of his defiant, self-confident nature when he boldly dismissed the alexandrine, the classical meter that had dominated French poetry for over three centuries. "You can imagine how surprised we were by this rebellious outburst," noted Valade. Little did he know what was yet to come. Soon, Rimbaud developed a reputation as the "savage" of the Latin Quarter, a child rebel who made the avant-garde look prudish. A notorious rule-breaker with a feral disregard, even disgust, for the niceties of Parisian decorum, he outraged decent society and fellow poets alike. He announced that Paris was "the least intellectual place on Earth", and proposed that the Communards should have blown up Louvre, a symbol of bourgeois tastes. His conversation was sporadic and obscene, his manners non-existent. At poetry readings, he shouted "merde!" and other profanities whenever he disapproved of his fellow poets' works. INGENIOUS VISIONARY Rimbaud's own poetry was, without a doubt, the work of a genius mind ahead of its time. He was the first poet to attempt expressing the inexpressible, in evocative language that bypasses conventional "meaning". He experimented with concepts such as the "colour" of sounds, the impact of sound over sense, and verse libre (free rhythmic patterns). He articulated symbolist ideas before symbolism became a movement; he was "the spectator to the flowering of (his) thought" before the surrealists embraced the notion of the subconscious mind and free-flow thinking; he was a poet-scientist who set down a credible theory for changing human existence itself. THE FAIRY AT WORK? Those familiar with the mind-bending effects of absinthe drinking may be tempted to attribute Rimbaud's ground-breaking visions to the influence of the Green Fairy. Whilst there is no doubt that Rimbaud enjoyed the company of the Fairy, or "absomphe" as he called her, we should remember that absinthe merely inspires genius; it does not create it. To fully understand Rimbaud's genius, we must realise that he was more of an explorer than a poet. By his own admission, poetry was but his favoured means of exploring the more fundamental aspects of life. Poetry was the medium through which he indulged in the "immense and rational derangement of the senses", a mental adventure that, he hoped, would provide answers to the Unknown. And if poetry was simply the vehicle that was to take him to his ultimate destination, the Green Fairy was merely a guide along the route, never the driver. Rimbaud didn't drink absinthe to get drunk, he drank it to liberate his mind and enhance his visions. This was in contrast to Paul Verlaine, his fellow poet, and many other artists of the time. THE ICON OF DISSENT During his short-lived (but brilliant) career as a poet, Rimbaud anarchic lifestyle mirrored his radical artistic life. He was the original room-trasher, the popular occupation of modern-day rock stars: a contemporary recalled how Rimbaud amused himself by smashing "all the porcelain -- water jug, basin and chamber pot," but also "being short of money, he sold the furniture". This apparently happened time and time again. Unlike those of most modern rock stars, however, Rimbaud's antics were not preconceived publicity stunts, nor were they random acts of anarchy. Just like his poetry, his lifestyle reflected his innermost desire to escape the frightening world of conformity and to re-invent reality. "Real life is absent," he proclaimed, and "I is somebody else," as well as "Love must be reinvented." Rimbaud is thought to be the first person of his time to publicly stand up for women's rights and, later -- during his time as a gun runner in the Horn of Africa -- to even propose the notion of "rights" for the local black population, a concept previously unheard of in France, a mighty colonial power of the time. Rimbaud's appeal as a determined revolutionary is such that in 1968, during the Paris Students' Revolt, students mocked up a photograph of him wearing jeans and mounted it on the barricades as an apt symbol of defiance. It has also been proposed that the extravagant American musician and occasional poet Jim Morrison may have faked his death in Paris and retraced Rimbaud's journey to Ethiopia. The anarchic child-poet was also claimed as messiah by a whole raft of later-day subversives, from surrealists to hard-core socialists. PAUL VERLAINE: ABSINTHE-SOAKED DAYS (AND NIGHTS) In contrast to Arthur Rimbaud, who was a genius who used absinthe as a prop, Paul Verlaine, his fellow poet and partner, was an absinthe drunk first -- albeit a very talented one. "I take sugar with it!" seems an innocent enough remark, but to Verlaine, this was his way of saying "hello" to just about anyone he met. It was "a sort of war-cry," one contemporary dryly remarked of the manner in which Verlaine usually delivered his peculiar salutation. The "it" which Verlaine took with sugar wasn't a cup of tea, of course; the "it" was the Green Fairy, absinthe. To Verlaine, absinthe was a way of life. CALMING POETRY, TURBULENT LIFE Born in 1844 -- ten years before Arthur Rimbaud -- Verlaine was to become the leader of the French Symbolist movement. He was the pioneer of free verse and an inspiration to scores of followers. Despite its vagueness and simplicity, or perhaps because of it, Verlaine's works remain a beautiful testament to his ingenious ability. According to the writer Graham Robb, Verlaine "never wrote a bad line" and some of his poems had "the strange power to calm a violent class of schoolchildren". Verlaine was much less reliable off the page. His life alternated between extended periods of drunken debauchery and shorter spells of sober repentance. His absinthe binges sometimes turned violent: he once set his wife's hair on fire, and threatened his elderly mother with a knife (he spent a month in jail for the latter incident, despite her mother's plea in court that he really was "a good boy at heart" ). The arrival of Rimbaud on the Paris art scene didn't help matters one bit. Verlaine had fallen for Rimbaud's poetry well before the young poet's appearance in Paris (the two exchanged letters when Rimbaud was still living with his mother in Charleville). When Rimbaud finally turned up, Verlaine fell for the boy, too. This was an affliction he never quite recovered from, even though their relationship only lasted about two years. It is probable that adolescent Rimbaud's interest in carrying on with Verlaine was a reflection of his innate anarchic desire to challenge convention. Verlaine, in contrast, was truly smitten, describing Rimbaud as "a sun that burns inside me that does not want to be put out" long after their paths had gone separate ways. FRIVOLOUS ADVENTURES While it lasted, their association rarely was a happy or a calm one, however. They left Paris for Belgium when Verlaine's marriage began to disintegrate, embarking on a two-year-long "frivolous adventure" (as Verlaine himself later put it) across Europe. They wrote, taught French, drank and provoked 'upright' society -- but they also argued and fought frequently. Rimbaud, who drank far less than Verlaine, slowly grew disgusted by Verlaine's near-constant alcohol consumption and bone idleness. Verlaine had become "impossible to live with", Rimbaud later complained, while Verlaine declared Rimbaud "a Demon, [not] a man!" with a terrible temper. The two parted company after Verlaine, in an absinthe-fuelled frenzy, lost control and shot Rimbaud in the arm. Verlaine ended up doing two years in jail as a result. In a later sober moment, Verlaine lamented their decadent, care-free lifestyle when he expressed a sincere regret over some lost poems of Rimbaud: "That dastardly Rimbaud and I flogged them along with lots of other things to pay for absinthes and cigars". END OF THE LINE Rimbaud stopped writing poetry at the age of twenty and set out to travel the world. In the seventeen years that followed (he died age 37 of a mysterious disease), he explored three continents, eventually settling down in Africa where he was a coffee trader, a gun-runner and even a Koran scholar. Verlaine spent his last years in the company of one Bibi-la-Purre, an umbrella thief by profession and, like Verlaine, a keen absinthe drinker. Together they killed their days in the cafes of the Latin Quarter, where Verlaine sometimes recited poetry to novice poets or tried to introduce prostitutes to the delights of literature. He died at the age of 50, broken-down and broke. ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ VERLAINE AND RIMBAUD: POETS FROM HELL The London home of Verlaine and Rimbaud, the enfants terribles of French poetry, is up for sale. A landmark of literary hedonism may be lost, says Christina Patterson Published: 08 February 2006 He lived in a squalid loft in a seedy part of town. He was often drunk, drugged and violent. He abused his friends, but relied on them to bail him out. Baby-faced and fiercely talented, this lyricist of love and death had a cult following and an angelic smile. "I know these passions and disasters too well," wrote Arthur Rimbaud in 1873, "the rages, the debauches, the madness." When he wrote those words, the great French poet was living in a house in Camden Town. The terraced house is still there, though in a dilapidated state and in an area that can only be described as bleak. Beside the front door there is a simple plaque: "The French poets Paul Verlaine and Arthur Rimbaud lived here May-July 1873". The words can't begin to do justice to the slice of turbulent history that lies behind those walls. Since the house is currently on the market, it is a history that is in danger of being lost. Arthur Rimbaud first met Paul Verlaine in 1871. Rimbaud was 17, Verlaine 27. Both were brilliant, volatile and utterly committed to the quest for the new, in art and life. Rimbaud was a young poet in search of a patron. Verlaine was a young poet in search of distraction - not least from his miserable marriage to Mathilde, whom he regularly hit. Verlaine's brother-in-law described Rimbaud as "a vile, vicious, disgusting, smutty little schoolboy", but Verlaine found him an "exquisite creature". He didn't seem to mind that Rimbaud rarely washed, left turds under one friend's pillow, and put sulphuric acid in the drink of another; not to mention that he hacked at his wrists with a penknife and stabbed him in the thigh. But by then, he was in love. The two of them ran off to Brussels and then London. Rimbaud was "delighted and astonished" by London. Verlaine was overwhelmed by the "incessant railways on splendid cast-iron bridges" and the "brutal, loud-mouthed people in the streets", but inspired by the "interminable docks. The city was, he wrote, "prudish, but with every vice on offer", and, "permanently sozzled, despite ridiculous bills on drunkenness". The two poets were often sozzled, too: on ale, gin and absinthe. Rimbaud's extraordinary sonnet "Voyelles" (Vowels), which gained an instant cult following, was clearly inspired by his experiments with "the Green Fairy". At other times, their drinking was less productive. They fought like cats, sometimes with knives rolled in towels. "As soon as mutilation had been achieved," according to Rimbaud's biographer Graham Robb,"they put the knives away and went to the pub." Their relationship ended with a slap in the face with a wet fish. When Verlaine came home one day with a fish and a bottle of oil, Rimbaud sniggered. Furious at being mocked, Verlaine whacked him with the fish, then stormed off to Brussels and threatened suicide. After pawning his lover's clothes, Rimbaud followed him and, in a Brussels hotel, they had their final row. With the gun he'd planned to kill himself with, Verlaine shot Rimbaud in the arm. He was jailed for two years. Throughout this time, however, both poets were producing work that would earn them a place in world literature. Verlaine wrote much of his Romances sans paroles; Rimbaud wrote many of the poems in Illuminations. Hailed as a masterpiece of modernism, the latter included the extraordinary polyphonic prose poem, "Une saison en enfer" (A Season in Hell). These were clearly not pieces tossed off in the pub. Rimbaud would spend hours polishing his lines in the British Library. He was, according to Robb, "ferociously self-disciplined". He may have smashed rooms up, but this was, Robb tells me, "partly a way of smashing the image that he was supposed to have. He came from the provinces and so was patronised by the Parisian poets. He never really did become a Parisian. And that is why it would be much more fitting to have a Rimbaud house in London than in Paris". For Lisa Appignanesi, one of a number of writers spearheading a campaign to save the Camden house, "it would be wonderful to insert their presence on to the London literary map, and to have a historical site that also thinks about the values of transgression". Rimbaud and Verlaine, she explains, "were both transgressive writers who influenced not only modernism but also the young for many generations, including the world of rock and pop". Indeed. Picasso, André Breton, Jean Cocteau, Allen Ginsberg, Bob Dylan and Jim Morrison have all named Rimbaud as an influence. And Patti Smith talks of her debt to the writer she dubbed "the first punk poet". Her song "Land: Horses/ Land of a Thousand Dances/ La Mer (de)" even coined the verb "to go Rimbaud". Even Pete Doherty, who has claimed Baudelaire as an influence, seems to share some of Rimbaud's proclivities. Like Rimbaud, he was a brilliant pupil who published poems as a teenager. And like Rimbaud, he's seems keen on opiates and blades, even writing poems in his own blood. But, for the Poet Laureate Andrew Motion, "there's something rather self-conscious in Doherty's attempts to conform to the Rimbaud model. It's all so attention-seeking". Julian Barnes, who is also involved in the campaign to preserve the house, included quotations from Rimbaud and Verlaine in Metroland, his first novel. Part One has an epigraph from Rimbaud's "Voyelles". Part Two has one from Verlaine: "Moi qui ai connu Rimbaud, je sais qu'il se foutait pas mal si 'A' était rouge ou vert. Il le voyait comme ça, mais c'est tout." ("I who knew Rimbaud, know that he really didn't give a damn whether 'A' was red or green. He saw it like that, but that's all.") "Rimbaud's 'Voyelles'," says Barnes, "is about how you see life at 18. The Verlaine quote is about how realism kicks in." It is, in other words, about growing up. Pete Doherty, take note. ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ YOU SHOULD KNOW ABOUT... ARTHUR RIMBAUD  By Craig Whitney [Oct. 2005] Had French poet Arthur Rimbaud been alive in the last 50 years or so, he would have been a rock musician. And from all indications, he would have had a lot of fans. Bob Dylan has repeatedly cited him as the key influence in his "chains of flashing images" lyrical style of the mid-'60s. Jim Morrison commonly signed autographs using his name, and wrote a fan letter thanking Rimbaud translator Wallace Fowlie. He inspired Patti Smith to quit her New Jersey factory job and start a rock band. Kurt Cobain named him as one of his favorite poets, and his widow, Courtney Love, read several of Rimbaud's prose poems at his funeral. The real Arthur Rimbaud was born 151 years ago today in Charleville, a town in eastern France just miles from the Belgian border. He was a conspicuously good student, composing Latin verse in his classes with astonishing rapidity and winning nearly all the prizes awarded in his school's annual academic competitions. At age 14, Rimbaud began increasingly turning his attention to composing French verse. His first attempts were, in general, unremarkable - technically brilliant but otherwise uninspired imitations of Victor Hugo and other notable poets of his day. The real breakthrough came in 1870 with the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War. With nearly all of Charleville's teachers serving in the war, the town's schools were closed for the fall term, and Rimbaud, who had grown to become increasingly revolted by the provinciality of his hometown, was transformed in these months of idleness from its prized pupil to its chief rebel. He wandered through Charleville, his greasy hair grown down to his shoulders, scrawling obscene graffiti on park benches and smoking his pipe upside-down, which for some reason was considered the most scandalous of the three.

Accompanying this newfound bohemianism, Rimbaud made a complete break with the influences that had fueled his early poetry. He wrote brilliant invectives against the flowery style of contemporary French poetry, wicked satires of his quaint hometown, polemics against the war, condemnations of religion and, especially, scathing attacks on his pious, domineering mother. What is most amazing is the tenderness and lyrical subtlety with which he did so, concealing a wealth of hidden meaning beneath the seeming simplicity of these poems. In "The Poet at Seven Years," Rimbaud contrasts his mother's petty tyrannies, and his quiet rebellions against them, with the first stirrings of his adolescent fantasy, imagining fantastic adventures and sea voyages from the quiet of his playroom. Invigorated by these early poetic triumphs, Rimbaud began to grow even more disgusted with his life in Charleville. He made several attempts to run away, following a friendly school teacher who was serving in Belgium, but was caught and returned to face his mother's wrath each time. Desperate, Rimbaud wrote two letters to the poet Paul Verlaine in Paris, enclosing several poems in his pleas for help in escaping Charleville. Verlaine, who was duly impressed with the skill of the young poet, wrote back immediately, saying: "My dear soul, come at once. You are summoned. You are expected." The newly married Verlaine and his wife, Mathilde, had recently moved in to her parents' home in an attempt to wean the middle-aged poet from his fondness for drink and, more importantly, his predilection for teenage boys. But when he learned that his young protegee was only seventeen - and not, as he had been lead to believe, in his mid-twenties - it was far too much for a man of his limited willpower to resist. The two embarked on a torrid love affair that would last for most of the next three years, and which Rimbaud would later chronicle in his brilliant intellectual autobiography, "A Season In Hell." For a few months Rimbaud and Verlaine made the rounds in the Paris cafes, mocking the smug self-satisfaction of its writers, driving a wedge between Mathilde's parents with their antics and in general making themselves the scandal of Parisian literary society. Under intense pressure from his in-laws to shape up or ship out, Verlaine, with much persuasion from Rimbaud, opted for the latter. For the next two years, the poets would divide their time between Paris, Brussels, London and Charleville, living off of Verlaine's inheritance in a series of bars and cold water flats. Unlike the deliberately provocative writings of Rimbaud, Verlaine's poetry, at least until the two met, consisted mainly of love poems to his wife, incredible less for their themes than for their unprecedented level of technical innovation. Under his influence, Rimbaud's poetry became not only more technically experimental, but more poised and meditative. Combining this with his increasing interest in mysticism, Rimbaud's poems took on a surreal, hyper-aesthetic edge, combining recollected events from his childhood with a visionary perceptivity for detail. In the poem "Memory," perhaps his greatest lyric, he delivers a cascading series of elliptical recollections from childhood, densely packed with detail and written in a carefully disordered style that brilliantly conveyed its hazy remembrances of things past. But despite the success of their collaboration, the sadistic, domineering Rimbaud and the hyper-passive Verlaine were simply too volatile a combination to make their poetic marriage last for more than a brief period. When Rimbaud finally resolved to leave Verlaine in 1874 to return to Charleville and finish the half-completed "Season In Hell," Verlaine shot him in a fit of desperation. He was later arrested, and when the nature of the two poets' relationship became apparent to the Brussels authorities, he was sentenced to two years' hard labor for attempted manslaughter. After finishing "Season," Rimbaud would go on to complete what would be the first book of prose poems in the French language, "Illuminations." At 19 years old, he gave up writing poetry for the rest of his life, spending a few years traveling and learning languages in Europe before resettling in East Africa. He spent the next 15 years in Ethiopia, working as an engineer, gun runner and, it is alleged, slave trader, before dying of cancer in 1891. While it is easy in some sense to dismiss Rimbaud as the arch-rebel of French letters or the teenage poet laureate, to do so would be to miss not only the incredible depth and richness of his poems, but the central importance of his place in the history of French poetry. Rimbaud's poems would go largely unrecognized for several decades after his death. But when, largely because of Verlaine's advocacy, they were rediscovered by Paris' young intellectuals near the turn of the century, he very quickly became the driving force behind the French symbolist and surrealist movements that would dominate the nation's verse well into the next century. But beyond any question of influence, Rimbaud's importance as a poet rests primarily in his effortless combination of subjective, personal detail with the visionary self-mythology that he crafted around it. That he did so with such deceptive simplicity is unprecedented not only for a poet of his extreme youth, but for a poet of any age. ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ FROM "MEMORY" BY ARTHUR RIMBAUD Translated by Wallace Fowlie Rimbaud's 1872 poem "Memory" draws on events from his childhood in rural France and delivers them in an extraordinarily brisk meter that evokes the elliptical, dreamlike nature of memory itself. I Clear water; like the salt of childhood tears; The assault on the sun by the whiteness of women's bodies; the silk of banners, in masses and of pure lilies, under the walls a maid once defended. The play of angels - No... the golden current on it's way moves its arms, black and heavy, and above all cool, with grass. She, dark, having the blue sky as a canopy, calls up for curtains the shadow of the hill and the arch. ... III Madame stands too straight in the field nearby where the filaments from the work snow down; the parasol in her fingers; stepping on the white flower, too proud for her; children reading in the flowering grass their book of red morocco. Alas, he, like a thousand white angels separating on the road, goes off beyond the mountain! She, all cold and dark, runs! after the departing man! ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~